At Fault Tolerant Tennis, we teach fundamentals. Today, though, we’re going to dive into a detail.

Why?

Because this detail, specifically, messes up so many players that it’s worth addressing on it’s own. In the same way that we’ve dedicated articles to just the low forehand, we’ll dedicate articles to other non-fundamental specifics, in cases when those specifics cause enough issues to be worth addressing by themselves.

During the forward swing on the forehand it’s actually impossible to execute a proper hip twist if the feet remain fully planted on the ground during your swing. The feet must come up off the ground, at least partially, in order for the hips to fully rotate.

The Role of the Back Foot

For the back foot, specifically, this can be challenging. During forehand preparation, you load up on your back foot, placing your weight on it, such that during the forward swing, you can drive off of it. However, you have to actually drive off of it, lest too much weight remain on this back foot as you swing, thereby preventing it from partially leaving the ground and freeing the hips to rotate.

Here’s the physical checkpoint that determines whether you (or your student) is doing it right: on almost every forehand, the back foot ends pointing at the target.

The back foot’s job is to press off of the ground, thereby initiating the kinetic chain. In order to do this, it must be planted on the ground, at first. This early weight on the back foot can be a double edged sword, though. That weight needs to, eventually, get off of the back foot, such that the back foot is free to rotate along with the hips. The feet are connected to the hips. When the hips rotate, the feet want to rotate as well, and when the hips end square to the target at contact, the feet want to be square, too.

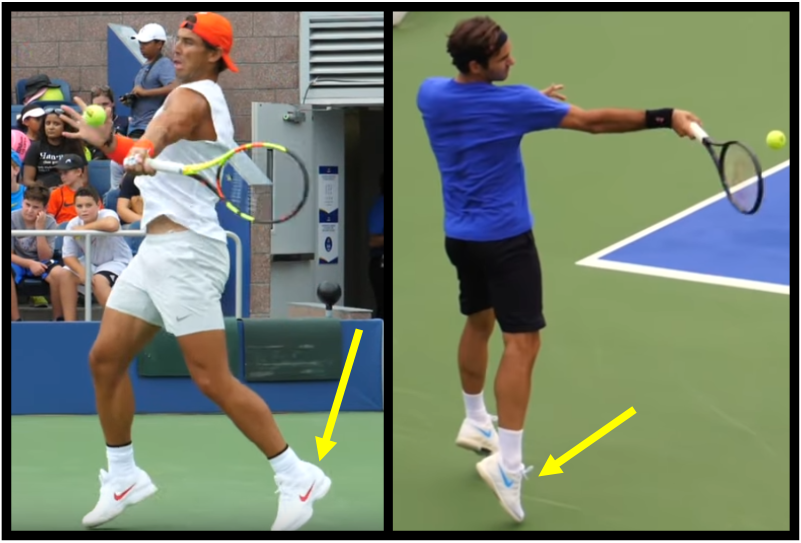

Look at the two images above, of Roger Federer’s and Rafael Nadal’s feet as each comes to contact. For each, the back foot is pointing towards their target. It starts facing away from the target (just like the hips), and then, as the player rotates during the swing, the foot itself naturally pivots back towards the net.

Should I Do This Consciously?

For some students, consciously thinking about the back foot ending towards the net helps them rotate. Specifically, this cue can assist with students who are under-rotating, students who are rotating too late, or students who are keeping too much weight on the back foot during rotation.

1. Under Rotation

When you under-rotate, chances are your back foot won’t get all the way around to the net, just like your hips. Often, if you think about “your back foot ending towards the net,” your body will naturally increase your hip twist in order to make that happen, which solves the fundamental problem, insufficient hip rotation, perfectly.

2. Late Rotation

Sometimes, a student will “rotate their hips,” in a sense, but they don’t actually drive their swing with that hip rotation. On a hip rotation which drives the stroke, the back foot needs to partially leave the ground, because if it doesn’t, there’s too much force on the ankle when the hips rotate.

The back foot needs to partially leave the ground, because if it doesn’t, there’s too much force on the ankle when the hips rotate.

When the hips, instead, engage late in the chain, they generate much less power; the hip twist isn’t an explosive hip twist, with the goal of driving the kinetic chain, but rather a weak twist with the simple goal of turning the body, because the student has a vague idea that the body is supposed to be turning. It’s possible to execute this out of sync hip twist without the back foot leaving the ground at all.

In this case, the “back foot at the net” cue can also help. When a student thinks about ensuring their back foot gets around, their consciousness moves to their hitting leg and their hip twist, the appropriate place when starting the forehand. This typically causes them to correctly initiate the swing by driving off of that foot, instead of adding an out of sync hip rotation later.

3. Too Much Weight on the Back Foot

Especially when using the non-hitting-foot-up footwork pattern, it can be easy to keep too much weight on the back foot, preventing it from sufficiently rotating. Again, simply thinking about getting the foot around usually solves this problem. Your brain understands that, in order for a foot to rotate, it needs to be deloaded. You’ll naturally increase your spring off of that foot in order to get it around towards the net.

The Hips Lead Foot Rotation

I’ll close with a point of caution concerning this cue. While it is extremely helpful, it’s important that any coach using it still understands the fundamentals behind it. This cue is a trick to get a student to employ hip rotation. It’s possible to rotate the foot without rotating the hips. This kind of foot rotation, absent hip rotation, is not in any way helpful to the stroke.

The cue isn’t merely an instruction, but rather a physical checkpoint for the student:

“Did your back foot rotate back towards the net? No? Then drive off of it a little more and allow it to come up off of the ground more, until it does.”

The cue is not:

“Use the muscles in the calf to twist your back foot towards the net.”

That said, the back foot’s orientation is a very useful detail for both executing and debugging the forehand, and learning how to cue it properly is a great tool to add to your coaching repertoire.

April 21, 2023

Thanks for these great articles! You say (paraphrasing): initially the back foot is pointing away from the net, along with hips. I’m wondering how this works with an open or slightly open stance. Should I rotate my back foot along with the hips initially as well?

April 23, 2023

Look at your favorite players on tour, and experiment with what they do. Djokovic is my favorite to have my students copy, when it comes to the open stance forehand. The back foot is typically totally sideways, before the stroke, or diagonally forwards/sideways.