Velocity is a measure of speed and direction. The sentence “my racket was moving fast when I struck the ball” is referencing the racket’s high velocity.

Acceleration, on the other hand, is a measure of rate of change of velocity. Not how fast or how slow is an object’s motion, but rather, is the object’s motion getting faster or slower?

The key to an explosive forehand is not merely to swing with high velocity, but rather it is to accelerate throughout the entire swing. Even in the final few milliseconds before contact, the racket should still be accelerating. Not only is it moving fast, but it is also getting faster and faster up until the moment of contact. That is late acceleration.

The Alternative to Late Acceleration

Many tennis players fail to accelerate late on the forehand. As a result, they have long, constant speed, slow swings.

Often, this player prepares well, drives off their legs well, is on balance when they swing, and, generally, looks pretty good as they strike the ball. It’s just that… the shot isn’t fast.

There’s a missing link late in their kinetic chain, and that missing link causes the player to only accelerate early, but not late. In the moments before contact, no acceleration is occurring, and the racket is moving at a constant speed.

Players who accelerate sufficiently late, on the other hand, produce swings which continue increasing in velocity until contact. We’ll be using Jannik Sinner’s world class forehand as an example of exceptional late acceleration.

The Timing of Elite Forehands

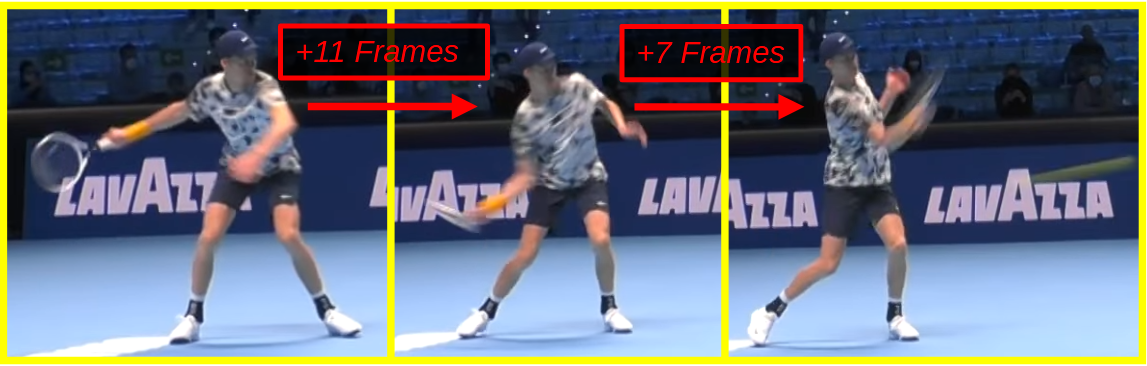

The image below is screencapped from a practice session between Jannik Sinner and Novak Djokovic, at the 2021 ATP Finals. I encourage you to watch it, as it provides a unique angle we don’t often see, an angle that’s crucial to understanding what’s really happening on a well struck forehand.

We’re discussing Jannik Sinner’s forehand today, but, if you watch the clip, you’ll see Novak implementing all of the same ideas.

The initial phase of Jannik Sinner’s forward swing is much slower than the final, explosive drive through contact. This is because, during the initial phase, the racket starts essentially at rest, and so, even when accelerated, its velocity is still close to zero. Acceleration is a rate of change of velocity over time, and therefore the longer a player can accelerate for, the higher their racket velocity will climb.

Jannik’s initial acceleration occurs as he transfers his weight forward and begins rotating into the shot. His hips and torso have begun to unwind, but because the racket started at rest, the racket’s velocity is still quite low, but acceleration has begun.

This initial move takes 11 frames.

Explosive Acceleration Through Contact

The contact phase occurs much quicker than the pre-contact phase. From the time Jannik’s elbow has just passed his hip, to the time his forward swing is completed, only 7 more frames have passed.

Not only is the contact phase shorter in duration than pre-contact, but the hand is actually covering far more distance during it. If the swing were performed at a constant speed, more time would be spent in the far greater distance contact phase than in the far shorter distance pre-contact phase. With Jannik Sinner’s elite stroke, we see the exact opposite.

Jannik’s swing is not performed at a constant speed.

This velocity increase is due to continuing acceleration. Jannik’s swing is not performed at a constant speed, but instead continues to increase in velocity all the way through contact.

The result is that the racket is moving faster and faster as the swing progresses. That’s why the early part of the swing, despite being shorter in distance, takes significantly longer than the contact phase – 157% as long, to be exact.

How do I implement this?

Louis Cayer, the LTA’s Senior Performance Advisor, advises players to imagine that, “the swing starts at contact.” Strange, right? How could we start the swing at contact – don’t we need to swing well in advance of contact to generate speed?

Literally, yes, but in practice, this cue is actually quite good. It’s helped many of my students break out of their constant speed swings, and harness their own late acceleration.

“Start at contact.“

Louis Cayer, LTA Senior Performance Advisor

It works because the most critical links in the kinetic chain are the final ones. On the forehand, you should contact the ball right after your chest engages. The pectoral muscles are one of the strongest muscle groups in the body, and they are responsible for late acceleration.

The earlier links in your kinetic chain are important, but mostly discretionary. You can accelerate early by driving off your back leg, and you certainly should, but it’s not fundamental to every stroke you’ll produce. Torso rotation is similar. If you have time, twist back as far as you’re comfortable, and then unwind that twist into your stroke, but if you’re rushed, like on a serve return, a much more muted turn-and-unturn is fine.

Late acceleration, on the other hand, is something you will always want. No matter what the situation, no matter how out of position you are, or how awkward the shot is, if you can get your chest to engage through your contact zone, your swing is going to feel better.

The Early Swing = Pseudo-Preparation

Watching some players, it feels like they believe they need to create 5000 rpms of immediate, swing starting hip drive to get anything on their stroke. This is not the case.

In fact, it really doesn’t matter how hard you drive through your hips if you can’t synchronize that initial rotation with your final drive through contact. Late acceleration is so important that the beginning of your forward swing should be performed in service to late acceleration.

Here’s how you implement this:

You’re in your final preparation slot, ready to swing. As you initiate, you have a specific manner in which you want to strike the ball. An intention for the contact you’re trying to create.

The beginning of your forward swing should be performed in service to late acceleration.

The initial part of your forward swing is performed in order to allow you to accelerate late through your desired contact. The early swing rotates your body and adjusts your balance, with the purpose of, yes, generating velocity, but mostly of preparing you for your final, explosive strike through the ball.

If your chest doesn’t engage as you twist forward, or if it does engage, but you don’t contact the ball right as it’s engaging, then you’ve lost the final, most important power engine of your swing. Tennis is a goal oriented sport, and your goal on the forehand is to coordinate the rest of your body to prepare, and then accelerate into, that final driving action through the ball.

Hip Drive and Early Acceleration

The real magic of hip drive is that it allows for early acceleration while also preparing you for late acceleration. During preparation, you turn your hips away from your target, so that you can turn them back towards the target during the forward swing.

Late acceleration is the primary engine of the stroke, and early acceleration is a powerful secondary goal that you attempt with sufficient time to prepare, which you will have on most shots. Preparation, like the early swing, exists in service to late acceleration. You aren’t turning your hips for fun, or because “that’s what you do.” You’re winding them back for the precise purpose of unwinding them into your shot to augment your late acceleration with early acceleration.

When you’re too time pressured for a motion that big – again, common on serve return – then don’t bother with it. Create a clean strike through the ball using the later links in your chain, accelerating late like you always do, and forgo your early acceleration on the altar of control.

Preparation, like the early swing, exists in service to late acceleration.

On most shots, you will have time to rotate, and you can inject extra acceleration with your hips without sacrificing fault tolerance. Because the racket starts at rest, this initial acceleration may not feel like much at first – your brain is perceiving your racket’s velocity, which is still close to zero, even though its acceleration, which you created with your rotation, is now positive.

When done correctly, though, the initial velocity your hips create stays with you deep into the motion. As long this early acceleration was performed in service to late acceleration, and you continue to accelerate all the way through contact, your combination of initial hip drive + late acceleration will result in a higher final velocity than just late acceleration would have. Early acceleration is a common way we inject effortful power into an already efficient effortless stroke.

What should it actually feel like?

This last few milliseconds before contact constitute a compact, explosive, forward drive of the arm, by which the racket is flung forward. The motion used is very similar to the one used to throw a baseball sidearm or submarine style. This forward fling starts at, or just in front of, the hip, and ends shortly after contact. It is brief. During it, the racket is far from the body, with sufficient space between the elbow and the chest, so as to allow the elbow to pass through the plane of the chest unimpeded.

This flinging motion occurs mostly passively – you should feel your chest firing, and once you feel that, you can try to fire it more by focusing on it, but it should primarily be firing automatically. If you have to consciously press to end your swing – if when you don’t consciously press, your racket doesn’t drive through the ball – something upstream has gone wrong.

This critical, final injection of velocity comes late in the swing process, only fractions of a second before contact. Any later, and the arm’s internal rotation would cause the string angle to close so much that the ball would fly straight down into the net. Figuring out exactly where this optimal contact point is – where the chest has just fired, but the string angle is still correct – for your swing, and your body, is critical to forehand success.

The force is applied quickly, almost all at once, not gradually and uniformly over the entire course of a long, looping forward swing. If you’re doing it right, you’ll be able to feel the explosive nature of the swing. It’ll be clear that the swing builds, and the racket is moving its fastest right before contact.

Many players attempt this final injection of pace too early in their swing process, with their elbow still stuck behind their hips, and/or with their hips not yet unwound towards their target. This ruins the efficiency of the swing, and can even cause hand, wrist, and elbow pain if you try to hit hard while pulling the hand forward from too far back. It is only out in front of the chest, away from the trunk, that the shoulder/arm/elbow/forearm/hand apparatus can freely and easily perform the flinging action necessary for effortless late acceleration.

Grip Relaxation as a Guide

We hold the racket loosely during our early acceleration on the forehand, because if we hold it tightly, no matter how explosively we move, the racket won’t be able to whip through the air.

Try the experiment yourself (with anything long and stiff, doesn’t have to be a racket):

Hold your chosen item tightly, and swing it. Now hold it loosely, and swing it. You’ll notice a clear increase in the speed of the object when holding it loosely.

We hold the racket loosely during our early acceleration on the forehand.

Your ability to maintain grip relaxation while accelerating early functions as a good barometer for whether or not you’re successfully accelerating late. When you’re properly flinging the racket into the press slot, and then through the ball, you won’t have a problem starting with a 4/10 grip tension, and only allowing your hand to tighten up through contact.

If, on the other hand, it feels like you can’t control the racket at 4/10 grip tension, you’re probably trying to pull the racket towards the ball from too far back in your motion. Twist farther around towards the ball before you try to hit it, and feel the chest engage as you do. Once you feel your pectorals working, prepare and time the swing such that, as you feel your chest really firing, your racket is slapping through the ball.

November 28, 2021

How can we implement this? I feel once the hip is initiated, the rest of the swing goes fast. The first picture set where 11 frames and arrow were shown, he has already initiated the hip turn, didn’t he?

November 28, 2021

Yes, that’s correct – the forward rotation has already started in that second image. The point is not to move your hand forward first, and then turn. The point is that your elbow should pass by your hip very early in that process, and much of the explosive turn should happen after the hand is already in front of you.

Many people have differing levels of arm-backswing. Rafa and Kyrgios, for example, pull their elbow back behind their back, while players like Federer and Karatsev don’t. The principle we talk about in this article unifies all those swings – the more volitional arm backswing, the more volitional arm forward swing is necessary to get into a position similar to the one Jannik is in here.

It’s hard to describe exactly what the proper swing feels like, but the important insight is that it doesn’t occur at a uniform speed, but rather it’s much faster through contact.

January 29, 2022

Why not explosively accelerate from the backswing rather than from when the hand breaks the plane of the hip as long as the wrist-arm-racket unit is loose, the fundamental rules are followed, the humeral-pectoral angle stays pretty much constant and the arm does not initiate the forward swing? After all, velocity = acceleration x time (forgive the mathematical inaccuracy).

January 29, 2022

Good question. If your humeral pectoral angle is staying roughly the same during the initial part of your swing, you should do exactly as you said. In fact, for players with very abbreviated backswings, like Alsan Karatsev, this is the case, and they almost can’t swing wrong, because they begin every stroke in a position from which you can just rip it forward.

For other players, though, there’s a lot more arm movement during preparation, and during the initial phase of the forward swing. For them, it’s critical that the arm gets out in front of the hips and chest before acceleration happens in earnest (getting to the humeral-pectoral angle you’re imagining), otherwise the kinetic chain doesn’t work properly.

January 29, 2022

Thanks. I finished the book which has been SUPER helpful and so much fun to implement. I am glad you said that the correct swing can come and go even in the same game-for me the same rally-and to experiment with the conditions that most often give the right result. When it works, it is magic and when it doesn’t: back to the drawing board.

February 9, 2022

Karatsev and Federer, with the very abbreviated backswing, you said “almost can’t go wrong”. Would you say this is the prototype for what you teach?

February 12, 2022

Definitely. The Kyrgios thing where you pull your elbow back and then whip it forward and out to initiate the swing is definitely flashy, but I’m not convinced it’s worth the extra motion.

Especially for adults who don’t have 10 hours a week to spend drilling their technique, go with a simple, Fed/Karatsev like swing.

February 3, 2022

For the sake of simplicity, assuming the vector of Sinner’s hand is a straight line towards the net and the total time of his swing to contact is 1/4 second, for the first 1/8 second, let’s say, the velocity of his hand is naturally slower than the remaining time to contact according to:

Velocity initial = Acceleration x 1/8 s is less than

Velocity final = Acceleration x 1/4 s.

Sinner’s hand may be covering more distance from hip to contact in fewer frames because of physics rather than conscious or unconscious late acceleration. Looking at slo-mo video it looks like he explodes from the get go.

February 3, 2022

I see what you’re saying about the physics. I agree that it’s possible what you’re describing is happening, but I don’t think it is, because the last leg in the kinetic chain hasn’t fired yet.

The last leg of the kinetic chain, the part where the arm is driven forward in front by the chest muscles, and as a result the humeral-pectoral angle closes, that part is the critical part we’re trying to get to happen later. The point of this idea is to delay when the humeral pectoral angle closes until our hand and elbow are out in front out in front of our body, rather than closing that angle while still sideways.

February 20, 2022

Your explananation of Sinner´s 2 phases of acceleration coincide completely with that of FAA you also analyzed, though the latter has that awesome trait of timing his elbow- hand preparation “in front”,” almost” in sync with the bounce. I would add that Rublev, Alcaraz, Berretini are in the same group of these past-the-hips “sudden” extra accelerators as an automatation in every forehand.

I don´t clearly see this in Tsisipas , Korda, Medvedev, Zverev, Norrie.

I´ve seen for instance that Monfils and Nole decide WHEN to apply this.

Do most of ATPs kind of regulate it?

PD: Apart from the extra speed you may get precisely that extra contributes with much more upward topspin (the Magnus force) that finally augments the inland margin of the ball and one´s confidence . Adds up for your Fault Tolerant concept 🙂

April 9, 2022

In my view, with no need of sequential photos I believe that Carlos Alcaraz visibly engages your concept “slower hand-elbow before hip plane level then max speed out in front of the chest”. The perfect model in my view.

(Rublev too, less visble though)

But in Alcaraz after his hand-elbow structure passes the hip plane level I clearly observe how that awesome shoulder turn goes kind of outwards during a sec fraction (as it has a brutal centrifugal force like a crosspunch in boxing) and then forwards at an incredible speed. Not in many is so noticeable (I’d say for sure in Federer and Nadal)

January 31, 2024

Hi John,

Excellent article! I an wondering if this ‘late acceleration’ rule also applies to serving. Thanks.

March 24, 2024

Thanks for another amazing article Johnny!

I have a more fundamental question: what does the late acceleration of raquet up to hitting the ball actually do to the ball?

Having watched a Federer ultra-slo-mo video of ball deformation on raquet contact, I ‘think’ that the forceful push deforms the ball more and therefore imparts more control + spin + momentum all at the same time. But I’d love to hear from you.

March 26, 2024

Good question. It increases racket velocity by recruiting more muscle in the swing. The swing becomes more biomechanically efficient, which leads to increased spin and power with the same level of effort. Racket velocity is all there is. No matter how you swing, the ball will be in contact with the strings for mere fractions of a second. We’re not trying to do anything literally during contact. Rather, we’re trying to swing in such a way so as to have the racket going its fastest right at that moment, in the direction we want.

This doesn’t always happen, by the way. Watch even the best players, and you’ll see them occasionally miss their contact window slightly. On those mistimings, their shot will come out much slower than it typically does. What’s happened there is that they’ve misread the ball. They set up their entire swing to accurately accelerate late, but then the ball didn’t actually end up at the spot they were aiming to throw their racket through, so they lost some velocity before the actual strike. The contrast between those swings, and their typical swings, showcases what we’re trying to do when we accelerate late and drive hard through the moment of contact.

July 29, 2024

You are really close, but realize it is not max speed you seek for contact, but more the max “G-force moment” created as the hand starts to pull the racket Across as it goes up thru contact. Good timing means you contacted at the optimum moment of strong G-Force created, therefore multiplying the Mass effect of the racket greatly for easy power. This is not late acceleration, but instead it is perfectly timed acceleration… most player snatch at the ball with early acceleration and some may wait too long for “Late” acceleration and therefore, miss out on some easy, controllable power….

August 5, 2024

I mostly agree with your sentiment. In practice, I see far more people accelerating too early, and then missing their late acceleration, than ones who accelerate after the ball is gone. That’s why this article focuses on late acceleration. Perfectly timed acceleration includes acceleration deep into the swing, up to the moments right before contact.