In the Barcelona 2023 final, Carlos Alcaraz hit nine drop shot winners against Stefanos Tsitsipas.

Nine. In two sets.

How is Carlos Alcaraz so unbelievably lethal with this shot, when most on the tour barely even attempt it?

There are two main reasons, one obvious, and one more subtle:

- Carlos Alcaraz’s forehand forces his opponents to play deep (obvious).

- Carlos Alcaraz is wrong footing his opponents with his dropshot (subtle).

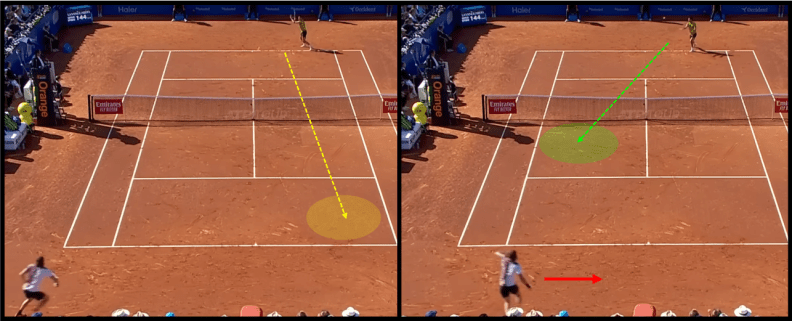

Throughout this article, you’re going to see images annotating many of the 9 dropshot winners from Barcelona, and in each case, you’re going to see these two concepts at play.

Why Defend Deep At All?

Playing well behind the baseline is very, very effective against a powerful hitter. Giving up space confers two major advantages:

- The ball is now easier to see. Since it must land inside the baseline, the bounce occurs far in front of a receiving player who is well behind the baseline, granting that player far more post bounce visual information than a closer player would get.

- You get much, much more time. The ball slows down a lot as it strikes the ground. A player receiving the ball from far back gets to wait through much more of the ball’s slow, post bounce flight before being forced to hit it.

This tactic is so effective, in fact, that if an attacking player only possesses power, they’ll never beat a tour level grinder, because the grinder will stand far behind the baseline, and the power player won’t be able to make the grinder miss.

Because defending deep works so well, if power were all Carlos Alcaraz had, most of the tour would beat him. Even though most players, even on the ATP, do not possess the vision and timing to handle a ball like Carlos Alcaraz’s from closer, it doesn’t really matter, because they will just back up to level the playing field.

Carlos’s dropshot is a strategic tool (of many) he uses to defeat this highly effective defensive tactic.

If power were all Carlos Alcaraz had, most of the tour would beat him.

Okay, but everyone already knows this. Alcaraz has a huge forehand. His opponents back up, and he hits the dropshot to punish them. This factor alone isn’t enough to explain nine dropshot winners in two sets against one of the most athletic people on the planet.

What if I told you that having a good dropshot actually lets you hit your topspin forehand harder?

Commit to the Contact Point

Groundstrokes are much easier to hit when they are not disguised. Hitting a forehand cross-court, for example, requires a slightly different movement than hitting a forehand inside-out, and, critically, the optimal contact point for cross-court is different than that for inside-out. When you disguise your forehand, you are compromising your kinetic chain in at least one direction, and when you forgo disguise, you get to generate extra racket head speed at the cost of predictability.

By utilizing the drop shot, Carlos Alcaraz gets the best of both worlds: disguise and velocity. He commits to the topspin contact point that’s optimal for the shot he wants to hit, sacrificing disguise for the ability to absolutely rip the ball. Without his dropshot, this wouldn’t be very effective: his opponent would just anticipate his shot and run there to defend.

Carlos prevents that by occasionally hitting a dropshot in the opposite direction.

Wrong Footing The Opponent

Unlike a topspin groundstroke, the dropshot is a touch shot. The “kinetic chain” on the drop shot (if you even want to call it that) need not include much – even just the arm can be enough, in cases. Due to this, we can play the dropshot successfully out of a wide array of different stances and contact points.

This is the brilliant innovation Carlos Alcaraz has brought to the tour. Set up for a big forehand, telegraphing where it’s going if you have to. Uncork it if you want – consistently ripping it, because you’re in perfect position. If your opponent isn’t reading your preparation, or isn’t playing deep enough to return the shot with quality, just rip the forehand all day long, without ever bothering to disguise it.

If they are reading it, drop shot the other direction out of the same preparation. They will instinctively shift their weight to defend the big forehand that their subconscious sees coming and will be completely unable to pivot back for the dropshot in time.

Carlos Alcaraz’s dropshot takes away his opponent’s last good defensive option. They have to stand back in order to see and react to his ball. Even when standing back, if they can’t read his preparation, they’re doomed, because he can hit both directions so effectively. Even when they are standing back and reading his preparation accurately, even then Carlos will simply dropshot in the opposite direction he would have blasted his groundstroke, and he’ll do it out of the exact same position he would have used to blast the ball.

Of course, he can do this equally well on both the forehand and the backhand and has an elite lob and passing shot to follow it up… because why shouldn’t he be a polished, complete player at 19 years old?

June 29, 2025

How does one disguise a forehand?

June 30, 2025

The best way is to hold your rotation, since because by far the easiest way to change direction is by rotating more/less. Try to rotate as late in the process as possible. Typically, the hips and trunk tend to show different max velocities and timings on cross-court vs down-the-line shots.

Because of that, though, hypothetically your opponent can read your preparation. (I suspect Andy Murray was world class at this.) That’s why the drop shot is so effective – it’s a shot that can be performed with a variety of awkward techniques, so you can literally set up identically to how you’d rip the ball cross-court, and then drop shot it down-the-line instead.

There are other ways to disguise – holding your shoulder back, using your forearm – this is why so many forehand winners close to the net are hit very slowly. You pay a velocity cost for disguise, but often, especially if your opponent usually guesses, it’s worth it. The longer in the process you want to disguise the shot, the more links of the kinetic chain you need to compromise on, and the slower you’ll ultimately hit. This is why the drop-shot is the ultimate tool for disguise, because hitting slower isn’t a detriment.

July 1, 2025

So, from my understanding, diguise comes from foregoing being precise with your rotations and setups in return for tricking your opponent. Say, I set up for an inside out forehand, but then I go inside in, I forego having the best setup for a inside in, and I attempt to hit that inside in, and while I may need to finish in a manner that allows me to make the shot(I find that I often have to finish over my head) and lose velocity in doing so, I gain the reward of wrong footing and potentially a short ball or winner. I think, however, when it comes to disguise, a player must be cognizant of not violating critical aspects of preparation such as probing or out, up, through while attempting to minimize the clues hip and trunk positioning may give. I think being able to do both at will is ideal depending on your opponent. If I’m playing a player with subpar movement, the Alcaraz strat is ideal. While if my player does move well or perhaps my forehand doesn’t yield enough of a window for a dropshot, misdirections may be ideal. Thank you for your insights!