In the 2011 Miami Final, Rafael Nadal hit a winner past Novak Djokovic that looked rather strange on TV (the point). The ball landed quite close to him, at least, close in the scope of professional tennis. It appeared to be the kind of shot that Novak had successfully retrieved countless times throughout his career, but in this instance, he didn’t move. The ball flew right past him, and he didn’t take a single step.

So what happened?

In a word: attention. Novak was distracted by the fact that he thought Rafa’s previous shot was out. That was all it took for the best retriever in the world to let a relatively innocuous ball blow completely past him for a winner.

Attention and Intention

Some players are naturally great retrievers, but for most, the skill doesn’t come so automatically. They’re vaguely aware that they’re supposed to watch the ball and move their feet, but that’s about it. The receiving loop transforms this vague understanding into a specific, repeatable, intentional process, which will drastically improve your receiving.

Here’s the loop:

- Look

- Split

- Explode

- Probe

- Hit

- Move

After this, the loop repeats. Look, Split, Explode, Hit, Move, and then we’re back to Look. The receiving loop is an attentive process. At each step, you are aware of what’s happening, locked in, either acting, or waiting for critical information so that you can at.

1. Look

Imagine it’s championship point in a tournament you really care about. Your opponent has an easy forehand, and you have to defend. You’re going to be hyper focused on your opponent, eyes primed for any sign or signal of where the ball is going to go, so that you can somehow return it and stay in the point. That level of attention, that level of visual focus on what your opponent is doing, is what you need to produce when receiving every ball, not just balls on important points.

The first step of receiving is to actively observe your opponent. Watch for your opponent’s contact, specifically. This requires intentional, deliberate attention; it’s more than just vaguely looking across the net. If you’re doing it right, you’ll be able to predict the exact moment they strike the ball, which is ties right into step 2…

2. Split

As your opponent is hitting, split-step. Your goal is to land right as you learn where the ball is going, and then explode towards where you want to be. The split-step’s timing is determined by the visual information you’ve gotten from Look. A good starting point if you’re new to actually split-stepping: split-step such that you’re at the apex of your jump when your opponent contact’s the ball.

We want to be on balance when we split step, able to easily explode in any direction as we land. Try to get stopped before you split. If you’re still moving from your last recovery, at least stutter step and slow down a little, because the more momentum you have when you split, the more awkward it will be to move in certain directions.

(The split-step can be skipped in very defensive situations. Instead of split-stepping, just guess where your opponent is going to hit, and move there before they contact the ball.)

3. Explode

If you’ve timed your split-step properly, you’re now landing and you know exactly where you need to go. Explode there. Hit the ground and fly off of it. You can practice this movement pattern in isolation. Land and explode right, land and explode left, land and explode forward, and land and explode back. You should be able to land and explode along any diagonal, or land and just adjust in place. All of these movement patterns are necessary for elite receiving footwork.

You should be able to land and explode along any diagonal, or land and just adjust in place.

Your focus during Explode is pressing off the ground as hard as you can, in order to generate as much force as you can, in as small an amount of time as you can, to propel your body towards where you need to be. Explode is the reason great tennis players’ shoes always squeak as they play. Even their small movements are not slow movements, they are very fast, explosive movements with quick starts and quick stops, and that quick stopping is what creates the squeak.

A great litmus test for how good a player is at steps 1-3 is how well they receive drop shots. If they’re missing Look, they probably won’t even notice the grip change until it’s too late. If they’re missing Split, they won’t get off their spot quickly enough, even when they notice what’s happening, and if they’re missing Explode, they’ll move for the ball, but won’t close enough distance quickly enough to play an effective shot once (if) they get there.

4. Probe

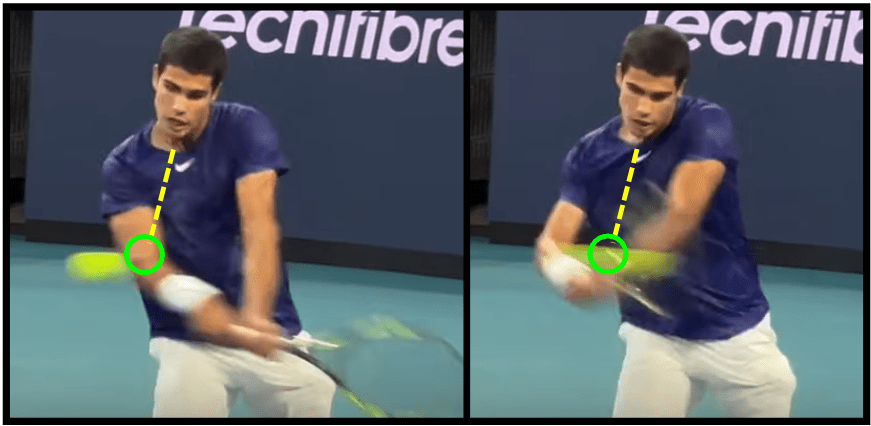

Actively receive the ball into the contact point that you want. Explode gets you moving towards the general area you want to be in, but now we need to make many small, fine-grained adjustments in order to prepare our body for the strike we want to deliver.

In order to probe, you must understand your own contact point like the back of your hand. You’ve internalized exactly where, in space, you want the ball to be, such that swinging at it is maximally comfortable. Probing is the act of using your eyes and your feet in order to set that position up.

Actively receive the ball into the contact point that you want.

Stroke preparation happens during this step. You’ll prepare differently on every ball, because every ball calls for a slightly different swing. As you probe the ball, you have a strike in your mind – a way in which you want the racket to hit the ball. Prepare however is appropriate for delivering that particular strike.

5. Hit

Hold your gaze still and hit the ball. During this step, your focus should be entirely on making clean contact with the strings. You might me moving during this step, you might be stationary. No matter what, there should be no thinking about your movement or receiving pattern while hitting. Your mind should either be completely clear, almost as if you’re meditating, or, alternatively, singularly focused on trying to strike the ball in a certain way. No thinking about the match, the score, or how you’re going to move after you hit.

Good receiving is about seamlessly context switching. Your focus switches from anticipating the ball, to striking it, and then back to anticipation again, in a matter of moments, and if any of those context switches are incomplete – if you’re still distracted by your movement while hitting, for example – you’re probably going to miss.

5. Move

There exists no relaxation or low intensity period after hitting a shot in tennis. After you hit, focus on your recovery with just as much intensity as you were focused on your movement to the ball. Recovery isn’t passive, it’s active. Explode back to the place on the court that you want to defend from.

Sometimes, you’ll want to defend from a spot close to where you hit, and other times, you won’t. Wherever you end your shot, the next step of receiving is to Move, even if it’s only a few steps, to where you want to be.

When you hit a cross-court shot, for example, you’ll usually want to prepare for the next ball in roughly the same place you hit from. When that’s the case, recovery is relatively trivial, and it won’t require explosive movement. In other cases, though, like when Lorenzo Musetti plays the drops shot pictured below, you’ll want to defend from a far different place than the one from which you hit, and you’ll have to move quickly to get there.

The Move step is easy to lose. When you’re grinding cross-court forehands, for example, recovery doesn’t require much movement. A common issue is that students get into a rhythm or groove with that pattern, a pattern during which recovery is very minimal, and in doing so end up losing the habit of aggressively, intentionally recovering, which is required by many situations in tennis.

The solution to this is to build a habit of intentional recovery in all situations, even simple ones. Even if you’re only a few steps away from your desired position, take those steps on purpose – an intentional movement towards the spot you’ve decided to defend from, all while looking across the court to see what your opponent is going to send you next.

1. Look

That’s it; we’re back to Look. As early as possible after hitting, we need to visually refocus on our opponent’s side of the court. Usually, this overlaps the previous Move step, but not always. For example, when playing a wide, defensive backhand slice, you’ll often need to turn your back to your opponent. In instances like that, your early recovery will occur while looking backwards, which is fine; get your head back around as quickly as you can to observe your opponent.

The Eyes Drive Receiving

The receiving loop exist in service to a single goal: set up your desired contact point. As the ball comes in, you must receive it. In another sport, that might mean catching or blocking the ball, but in our sport, it means striking it with a high velocity swing, and that necessitates the ball is a certain optimal distance from your body in order to perform the swing effectively.

The first step of the receiving loop is Look, but the eyes drive the entire process, not just the Look step. Split is timed using visual observation of your opponent. During the Explode step, you are exploding for the purpose of probing the incoming ball, which you’re watching while you move. Somewhere between the Explode and Hit steps, you’ll need to watch the ball bounce, and only once it’s time to actually swing should the eyes relax, the gaze almost turning off and held still, while you produce your stroke.

After Hitting, the eyes lock onto the opponent again, ideally during the following Move step. Re-lock onto your opponent, Look across the net at how they’re playing the ball you’ve just hit them, and then prepare to time your next Split.

Practice the ENTIRE Loop

Non-professional players frequently unintentionally neglect parts of the receiving loop as they practice. The most common manifestation of this issue is the feed in a coach-run tennis class. The feed is slow and predictable, so your success rate can be decently high without receiving it properly, and due to that succes, a lack of receiving technique on the feed often goes unnoticed.

The most common manifestation of this issue is the feed.

The entire first half of the receiving loop typically gets neglected on a feed.

Look: Even if you aren’t watching the coach strike the ball, you’re not going to be late, because the feed is so slow.

Split: The feed will come right to you. You don’t need the early elastic energy boost from the split-step to get to your spot.

Explode: Again, because the feed comes right to you, a few, relaxed, non-explosive steps are sufficient.

Herein lies the problem. The entire beginning of the receiving loop is unnecessary on a feed, and you might hit 200 feeds over the course of a 2-hour class. That’s 200 repetitions where you are habituating receiving a ball the wrong way.

The solution is to perform the entire loop even though it’s overkill for the feed. Watch your coach’s feeding motion as if they were your opponent. If you can, split, even though the extra boost really isn’t necessary. If you can’t split, at least start in an athletic stance. Take your one or two adjustment steps explosively, not casually, and actively probe the ball, even though, since it’s coming right to you, you can probably just auto-pilot it. Receive feeds like you’d receive any other shot, and you’ll get much, much more out of them.

Tennis Points Should Be Engaging

Receiving a tennis ball is a fundamentally visual and attentive process. You should be dialed in and focused for the duration of the point. Your mind might process 20 different non-verbal thoughts, based on what you’re seeing and feeling, as the point is playing out, each of which helps you execute slightly better. Thoughts like “I’m a little too close to this one” or “he’s about to slice that ball.” When you’re engaged, these kinds of little insights flash across your awareness constantly.

When you’re engaged, these kinds of little insights flash across your awareness constantly.

I want to reiterate that these thoughts are non-verbal. It’s more like noticing than it is thinking. I’m only verbalizing them here because, well, it’s an article, so I have to communicate with text, but, during a tennis point, these thoughts do not exist as sentences, but rather as evanescent, formless pieces of knowledge. A brief intention that you should put this volley away cross-court. Perhaps the shot’s even off your racket before your consciousness realizes what you’ve decided to do.

Verbal thoughts are far too slow and distracting to use during a point. You get ONE, maybe, and that’s it. Normally, working on one verbal idea like “move your feet” or “breath” won’t ruin your game, but trying to work on 2+ at once definitely will.

The “Hit” Drill

Attentive, intentional receiving has to be practiced, just like every other skill. Here’s a great drill to try: next time you play, say “hit” at the moment your opponent’s strings strike the ball, and I mean the exact moment, not a moment sooner or later. This will force you into the level of attention necessary for elite receiving in tennis. Make that level of attention a habit, and your game will tremendously improve.

April 10, 2024

So glad you are uploading articles again. We missed you!

April 13, 2024

Agreed – I await the net post eagerly.

April 13, 2024

I’m speculating, but I suspect that the failure to pay *this level* of attention is the greatest reason the vast majority of adult amateurs never improve significantly. They (We) devote far too much mental attention to stroke mechanics (internal focus) rather than focusing on movement and the ball (external focus) with the level of intensity described here.

April 14, 2024

I think you’re exactly right. There are three fundamental skills in tennis – swinging, moving, and seeing. Most adults who take up the sport spend 90% of their energy on swinging, and their swinging really does improve, but they unknowingly neglect moving and especially seeing, to such a degree that their overall game doesn’t.

April 14, 2024

As a beginner-intermediate player, I feel gaze at the ball sufficiently long time (before moving up to see the opponent and where the ball goes) also helps to hit the ball with the sweet spot. Is this correct?

April 14, 2024

Yes, that’s exactly right. “Gazing at the ball for a sufficiently long time,” as you put it, is a technique called “The Quiet Eye” coined and written about extensively by visual researcher Joan Vickers.