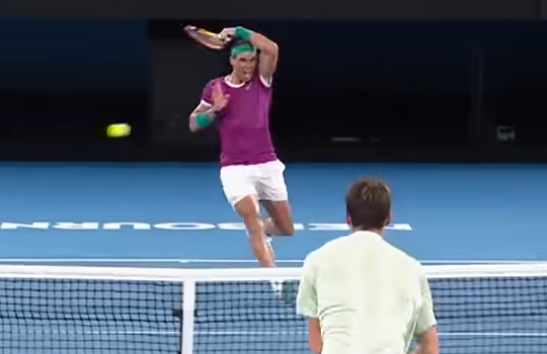

The “buggy whip forehand.”

The “reverse forehand.”

The “over the head follow-through.”

It goes by many names, but my favorite pays homage to the first man to really abuse it on the pro tour – “Rafa-Style.”

Nearly every player on the tour, both male and female, employs the Rafa-Style forehand in some instances, and for some, like Rafa himself, the stroke is a staple of their game. So what is it, anyway?

The first thing to understand about the Rafa-Style follow-through is what it isn’t – it is not our primary way to attack low balls, or to add spin to our shots.

Players follow through above the head due to increased volitional upward arm movement during the forward swing. A swing with that extra verticality will impart more topspin than one without, and a swing like that will be more likely to drive the ball up, but the above-the-head swing is not the ideal way to accomplish either of those goals.

As we’ve discussed many times on here, volitional arm movement isn’t as powerful as core movement, because the muscles that pull the arm up are far weaker than the strong muscles in the hips and trunk. In an ideal situation, we create our swing by using our strong trunk muscles to fling the arm forward.

So what is it for?

The Rafa Style follow-through is for catching the ball late.

The optimal contact point on the forehand is well out in front of the body. When we strike the ball there, we are able to initiate the swing with either our abdominal rotation, or if we have more time, our back leg drive, and in doing so explosively fling the racket out away from us, through the ball.

If we catch the ball farther back, this doesn’t work. We can try to twist around and let our racket fling out through the ball, but we won’t be able to, because by the time we get to the ball, we’re not in the forward fling stage of our swing yet.

The solution is to follow-through above the head.

When we’re late, and we still initiate the swing with our abs, we need the forward flick part of the swing to happen earlier. In order to accommodate this, we pull the racket up, and use the vertical space above our head to complete the movement.

Normally, we allow the racket to flick forward through the horizontal space in front of us. This is ideal for driving the ball, and, best case scenario, it’s what we want to do. But in a pinch, we can use the vertical space above our head instead. We twist, pull the racket up while we do, and in doing so are able to still recruit our twisting chain, and get most of that energy into the ball.

The Rafa-Style follow-through will always generate less pop than an identical acceleration that was able to flick forward instead of up, but that sacrifice is very often worth it, because the ability to catch the ball late provides many surprising advantages, which we’ll discuss next.

1. Fault Tolerance

In order to be a useful match shot, or forehand must succeed when executed imperfectly. This means, among other things, that it must succeed when we’re accidentally late. The Rafa-Style follow-through allows this.

You move to the ball, prepare, initiate your swing… and you quickly realize it’s too far back to allow the racket to naturally flick through it (luckily your tracking off the bounce was good enough to notice this in time to adjust). You’re late, now what?

In order to be a useful match shot, or forehand must succeed when executed imperfectly.

Well, immediately after you twist your abs forward, you can just swing the racket up instead of forward, and your stroke will still work. The ability to do this in real time creates fault tolerance – you can be late by accident, and stay in the point.

2. Offense

Fault tolerance and offense go hand in hand. The more fault tolerant your stroke – the bigger the mistakes it can tolerate without failing – the higher degree of difficulty offensive shots you can attempt.

Think of it this way:

If you go for difficult offensive shots, you’re going to mess up. You’re never going to hit them perfectly, because they’re so challenging.

But guess what, if your stroke works even when you mess up, then you can attempt these difficult shots, mess up, and still win those points.

It doesn’t matter that you rarely strike the shots perfectly, because even when struck imperfectly they still work. It is in this manner that fault tolerance allows us to be more aggressive.

The Rafa-Style follow-through is one of the reasons that Rafael Nadal has the best change-of-direction down-the-line forehand in the world. This shot is notoriously difficult to time, and Rafa also often times it imperfectly.

But it doesn’t matter.

When he times it perfectly, he drives through the ball, his racket flicks around his shoulder, and he hits a winner. When he’s late, he finishes over his head instead, and, most of the time it’s still a winner.

Rafa explodes forward to these shots, taking them extremely early. This guarantees his opponent is out of position, but the payment for that advantage is that it also greatly increases the shot’s difficulty. His proficiency with the over-the-head follow-through, which allows him to accommodate late contact, is the key that unlocks fault tolerance when doing this.

3. Disguise

It’s easier to hit a target without disguise. If you allow yourself to prepare your body differently for different targets, you can actually take the exact same swing for each one, and just adjust your preparation so that the same exact swing goes to a different target.

But in a match, we need disguise – a shot isn’t useful if our opponent knows where it’s going.

This means that the ability to hit late and succeed is a huge advantage. We’ll use a very common Federer trick as our example here – disguising the forehand out of the backhand corner.

Federer runs around the backhand, and prepares for an inside-out forehand. Because he’s prepared for an inside-out forehand, he’s preparing for a contact point that is later than would be ideal for an inside-in forehand.

So how does he, in fact, strike the ball inside-in when he wants to? If you’re following the theme of this article, you already know:

He finishes above his head.

The ability to successfully strike the ball late allows him to successfully strike an inside-in forehand using a contact point much closer to the optimal inside-out contact point. Any power he sacrifices in not being able to fully drive through the shot is more than made up for by the disguise.

Should I Practice It?

Probably not directly. At least, you shouldn’t practice routinely catching the ball late.

What you should practice are the applications of the Rafa-Style shot. Practice disguising your forehands – preparing for an inside-out contact point, but then using the Rafa-Style finish to pull it up the line instead. Practice taking more risk on offense, and adjusting with the Rafa-Style follow-through when necessary.

In practice, make a note when you utilize this follow-through – “huh, I was late there.” You don’t want to be late. If you practice being late, then when you’re later than you want, you’ve already used up all of your margin for error, and you’ll miss.

That said, you do want to train into your muscle memory that, on the off chance you’re late, this is how you strike the ball. You’ll stay in the point, and then try not to be late next time.

March 6, 2022

Thank you so much for this article. Many times I found myself with a vertical follow through like Rafa style and I usually chastise myself for a bad follow through. After reading this article I understand why I did it although I did not realize it at the time. Now I will tell myself it is ok to do it, but also realizing that I did it because I am late and I can adjust and correct.

March 29, 2022

Thank you for sharing your thoughts on the Rafa follow-through in this article.

From my short experience (1 year of playing lefty) trying to model Rafa’s game I can say that the Rafa follow-through is indeed super fault tolerant. It is the most fault tolerant way to hit a forehand I’ve experienced with since you’ll clear the net 99.90% of the time due to a higher launch angle and you’ll rarely miss long thanks to the extra spin and, as you mentioned, the reduced power.

It is so fault tolerant when you’re late on a ball that all players on the tour use it when they are under time pressure BUT Rafa uses it in virtually ALL situations. It’s a well-known fact that he finishes across his shoulder only in practice sessions. You can see it for yourself on YouTube. During matches he almost always finishes above the head (be it on clay or on hard courts) even when he has plenty of time to hit.

I believe it is because he can still produce massive power even with his follow-through but moreso because it allows him to generate SIDE SPIN and ANGLES to push his opponent back and off the court to their weaker stroke, the backhand. No other follow-through can create that kind of side spin and angled shots. The height, top and side spin along with the angles generated have devastating effect on a righty’s bakchand without the need for power.

April 1, 2022

You’re totally right that he rarely finishes around his shoulder in matches, although he occasionally does in offensive situations, like the one pictured in the article.

Also, yeah, the fault tolerance of the over-the-head follow-through is insane. I will point out that Rafa is insanely strong, and so he can get away with driving the ball more with mostly just his arm than most people can.

That said, I think it’s a common misconception that the over-the-head follow-through enables angles that are otherwise impossible. With a slightly more out-in-front contact point, those angles are possible with an around the neck, shoulder, waist, or even hip follow-through. Check out some Leylah Fernandez or Iga Swiatek for an example, if you’re curious.

Anyway though, Rafa is an amazing player, and maybe he just knows something we all don’t, which is why he goes over the head so much. I still prefer to teach a more out-in-front contact point as the default, but I wouldn’t blame ya at all for Rafaing it all the time. Like I always say, experiment, and if it’s working, it’s working.

April 5, 2022

Thank yo for your thoughtful reply Johnny.

I’ve been experimenting with the reverse/Rafa finish for a year now, and it’s really been my “get-out-off-jail card” in many many situations. It’s slowly becoming my go-to finish when I play lefty (not so when I play righty) in all situations. Like you said, it’s good to experiment! But, yeah I could never crush FHs with this reverse finish, it’s unbelievable what Rafa is capable of… So much strength!

I bought your book and read all you posts, and I need to tell you that being introduced to the “tilting” of the shoulders has really been a paradigm shift for me. Improved massively both my understanding of tennis and my performance.

So, a big thank you!