At the start of our forehand power checklist, we distinguished between effortless power and effortful power. Obviously, in order to hit really, really hard, you have to use both, but the manner by which you employ them isn’t immediately obvious.

For every player, there exists a physical upper limit to how much effortful power they can inject into their stroke before their margin for error drops off a cliff. If they were to try to hit any harder than that, their miss percentage would skyrocket. The speed at which they can hit while staying below this effortful power threshold constitutes their upper limit for speed on match usable forehands.

You cannot successfully inject any more effortful power into the shot after this point, no matter how hard you try. Even if you’re focusing on all the right things – driving off your back leg, winding your abs up during preparation, whipping your torso around with your off-elbow, and staying relaxed – at a certain point, trying to hit harder will cause your success rate to crater.

The Power Limit

The cratering success rate when trying to use too much effortful power can manifest in a few different ways. First off, as a general rule of physics, the faster your racket is moving, the harder it is for you to time your stroke. With a faster swing, a contact zone of the exact same length now constitutes less time during which correct contact can be made.

Even if you’re focusing on all the right things, at a certain point, trying to hit harder will cause your success rate to crater.

This is one reason that baseline, mechanical level fault tolerance is so important – the more fault tolerant your stroke is, the harder you can swing, even though doing so often introduces small timing faults. Since the shot is struck in a fault tolerant manner, these small faults don’t break it Even when you hit hard, you can still maintain a sufficiently high success rate, because your shot doesn’t have to be timed perfectly to succeed.

Second, any small mechanical flaws are magnified by racket speed. Other small non-timing execution mistakes, like a slightly incorrect string angle, or a slightly sub-optimal contact point, will have their effects magnified at greater swing speeds – a ball that would have landed on the line at 80% effort might fly a few inches out at 100% effort.

Lastly, and probably most importantly, it’s not actually easy to maintain fault tolerant mechanics while trying to inject a massive amount of effortful power. Most of the time, after a certain point, conscious effort to “try and hit harder” manifests as tightness in your hand, tightness in your arm, and an overall jerkiness and discoordination in the rotational kinetic chain. The result of this, of course, is that despite your mental perception of putting in more effort to swing faster, you’ll actually end up hitting the ball slower than if you’d put in less effort. The rotational kinetic chain is your racket speed engine, and when those mechanics are compromised by extra tightness and discoordination, that engine stalls.

Your Mind Will Lie to You

Unless you’re very experienced, this limit on your useful effortful power is likely lower than you think. Your mind will lie to you. It will ignorantly (and arrogantly) inform you that, if you just dial up the effort another few notches, you can crank out an extra 5 or 10 mph. In all likelihood, you can’t.

In order to hit really really hard, you need to gain 15 pounds of muscle, and then swing the exact same way you swung before.

You have to experiment during practice to determine what level of effort corresponds to the hardest consistent shot you can hit – shots below an 80% success rate are mostly useless in tennis, except out of defensive positions. Once you find this level of effort, you need to train what it feels like into your memory, and you need to cultivate the discipline to stay under it during you matches. That’s your top speed. For now, at least.

If we can’t inject more effortful power into our shot without ruining our success rate, then if we still want to hit harder, there’s only one variable left to tweak – effortless power. In order to hit really really hard, you need to gain 15 pounds of muscle, and then swing the exact same way you swung before. That’s it.

Once you’ve mastered everything in this book, and you’ve found your personal level of controllable effortful power, you’ve done all you can with respect to power at your current physical strength level. You can no longer hit harder by trying to hit harder. At this point, you’ll be able to hit hard, for sure. But the athleticism required to really crack it constitutes more than just proper technique.

TV Strikes Again

Strength is a very under-rated part of tennis athleticism, partially for good reason. First off, technique really is, more important, categorically. For 95% of players, the most efficient way to improve is to develop better mechanics. Time spent on strength training would be largely wasted with respect to their tennis game, since their mind isn’t really capable of effectively harnessing any new strength they’re building into a measurable advantage on the court.

In the same vein, a strong player with poor mechanics will lose to a weaker player with excellent mechanics ten times out of ten. That’s just the way tennis strokes work. If the choice is one or the other, strength or technique, technique will win every time. However, at the highest levels of the game, of course, this is selection a false dichotomy. In order for any player to really unlock their potential, they need to develop both strength and technique.

Back in our discussion of “wrist lag,” we discussed how misleading visuals on TV often lead to common misconceptions in tennis. Under-emphasis on strength is another of such misconceptions. They say that when it comes to modeling, “the camera adds 10 pounds.” Well, when it comes to tennis players, the camera subtracts 10 pounds. Through your TV, it’s actually very difficult to see just how strong the player’s on the tour really are.

Take Roger Federer for example. When you think of him, what are the first athletic traits that come to mind? Coordinated. Graceful. Fit. Quick. But not strong. It’s just a trick of the cameras, though – just like the model you’re seeing on TV isn’t fit, but rater is unhealthily skinny, the athlete you’re seeing on TV isn’t merely fit, but is actually also unbelievably strong.

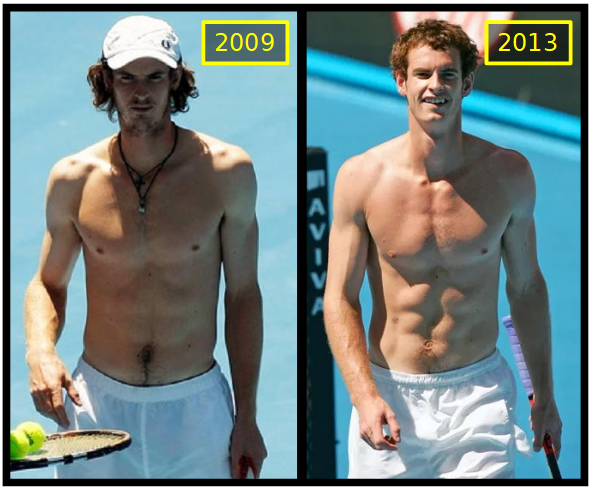

Andy Murray further proved the importance of strength when he transformed his body prior to winning his first Wimbledon title in 2013. Check out the before and after below, comparing his upper body musculature in 2009 to that in 2013. He’s lean in both, he’s fit in both, but he’s significantly stronger in 2013. Now, sure, this is just one data point – a single tennis athlete who used strength to transform himself from great, to all-time great – but it’s still quite significant.

Don’t let the TV deceive you. Once you’ve mastered your fault tolerant technique, the tennis specific part of your power generation is essentially complete. The next step has nothing to do with tennis specifically. The next step is to get stronger.

October 24, 2023

wow!

October 24, 2023

So which exercises can I do to strengthen my ground strokes?