“Rhythm” in tennis means different things to different players, but here’s how I’ll define it:

You are “in rhythm” when your neurological pattern has calibrated itself in the near-term.

As you get “in rhythm”, small timing errors, perception errors, and calibration errors, that existed in, say, your Forehand Function, have now worked themselves out, and a more precise version of the function is running. Insofar as your brain continues to run this refined version of the Forehand Function, you hit better forehands and consider yourself in rhythm.

How Matches Destroy Rhythm

There exists a waiting period of about 30 seconds between tennis points, and during that time, you hit zero balls. There’s a changeover every 2 games, during which you rest for 90 seconds and hit zero balls. At every level, most points contain fewer than four shots, either because serve quality is high, return quality is low, or both.

Taken together, this means you hit only about 5 shots per minute while playing matches, if that (including the serve). Imagine practicing like that. Count to 12 seconds. Hit a shot. Count another 12 seconds. Hit a different shot.

You hit only about 5 shots per minute while playing matches.

When it comes to specific shots, like a forehand or a backhand, the prospect of rhythm is even bleaker. Your five shots might be a serve, a blocked return, a running forehand, an easy forehand, and a backhand slice. An entire minute passed, and you didn’t hit a single drive backhand. The shots you did play, you played only once.

Therefore, in order to win matches, your shots must succeed while neurologically-cold.

What Rhythmless Dominance Looks Like

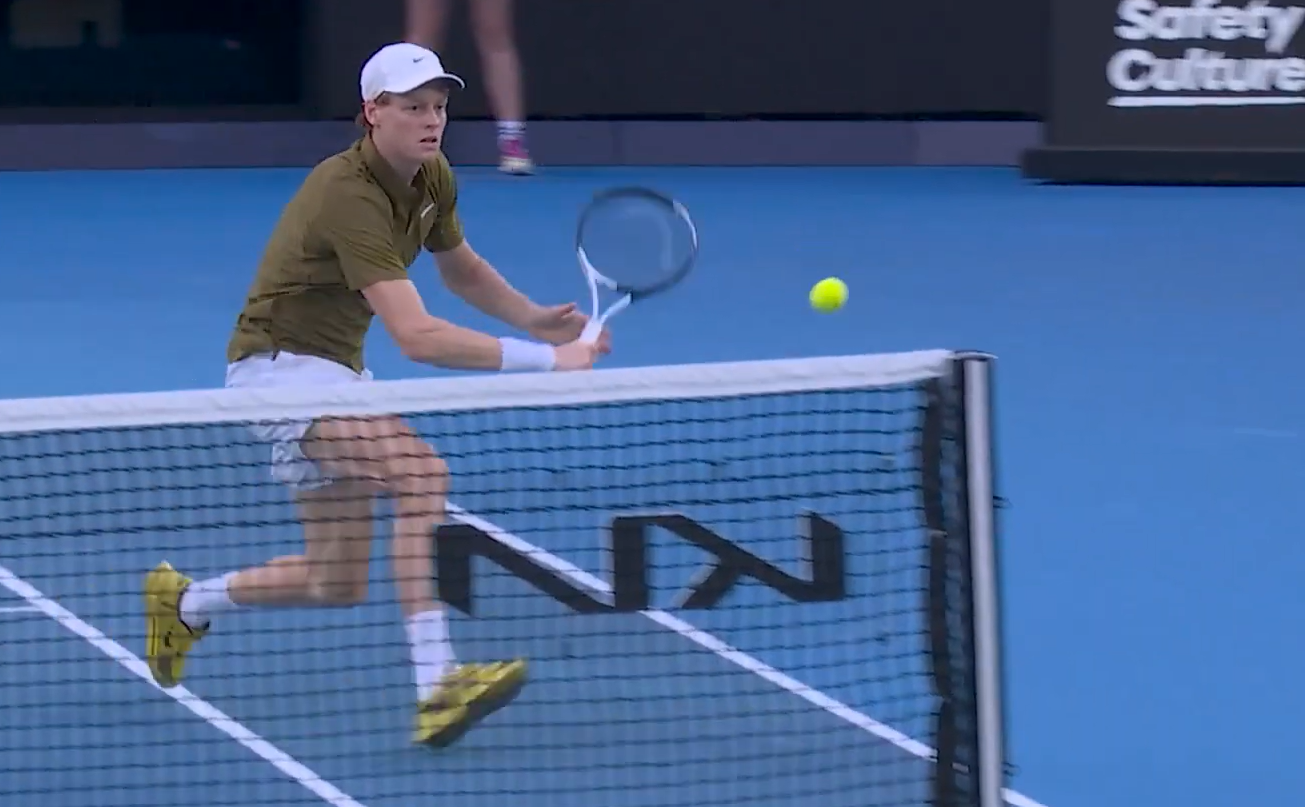

Here is a 2-game stretch of brilliance from Jannik Sinner, from 2-1 to 4-1 against Ben Shelton in the 2026 Australian Open. It runs from 21:24 to 32:46, for a total of 11 minutes and 22 seconds.

In that time, Jannik hit the ball 38 times, for an average of one hit per 18.1 seconds, or just over 3 shots per minute. Below are the shots Jannik played multiple times during this stretch. Notice how even the most frequent shot – the forehand with the feet set, was played only 6 times in 11 minutes.

- Forehand Return – 5/5

- Backhand Return – 4/4

- Forehand (feet set) – 5/6

- Backhand (feet set) – 3/3

- Forehand (stretch+slide) – 2/2

- Backhand (stretch+slide) – 3/3

- First Serve – 2/4

- Second Serve – 2/2

- Forehand Drive Approach – 2/2

Even if we pool the forehands as a whole, which is a little ridiculous, because returning a 120 mph serve with the forehand has little in common with using it to attack a short approach – still the shot was hit only 16 times, or once every 43 seconds.

Below are 7 shots Jannik played only once in the entire 11 minute period.

- Backhand sprint forward slice passing shot – 1/1

- Forehand sprint forward slice passing shot – 1/1

- Forehand vs No-Pace Floater – 1/1

- Backhand slice lob – 1/1

- Forehand slice lob – 1/1

- Backhand pass – 1/1

- Backhand stretch slice return – 0/1

Of these, both sprint-slide-slice passing shots won him the point. The backhand topspin pass won him the point, and he successfully crushed the no-pace floater with his forehand, also winning the point. Four points during this 2-game stretch were won by Jannik Sinner because he successfully executed a high-degree-of-difficulty shot, despite only playing it once in 11 minutes.

Implications for Development

Our practice courts are broken. The skill of match tennis is being able to execute a sliding slice passing shot into the open court on demand, without getting to hit 5 practice ones beforehand. It’s being able to destroy a floating ball with your forehand, once every 10+ minutes, on command.

And what are we practicing? The same cross-court, on-balance contact over, and over, and over.

During practice, you have one goal – improve your skill of using the racket to make the ball do what you want. Improve your connection to the racket, your awareness of how to use it, how it moves, what it feels like. Improve your eyes and your brain, your ability to correctly anticipate and react to the balls in front of you. Improve your movement, your balance, your control over your trunk. Connect the pieces together. Connect your eyes to your feet, connect your contact to your trunk. Make your tennis-playing system more and more robust, resilient, and generally adaptable.

The skill of a tennis match isn’t being able to hit 20 balls cross-court. It’s being able to do things you’ve never done before, on command, under pressure, and with only one try.

Build your system accordingly.

February 22, 2026

I think one foundational component to this is maintaining executive function and focus. I think going into the match with a set of expectations on play is highly disadvantageous because your brain will flag when a shot is what you ideally want(i.e. set forehand) vs. what’s new and surprising(returning a low slice on the backhand slide that landed at the service line) which creates a negative reaction as you feel reality not meeting expectation and losing control.

Tennis players should approach tennis the same way squash players approach squash. Squash moves way faster, so although patterns of play do develop, the game often ends up being a chase for the ball, shot, and receive loop. Whereas, since tennis has slightly more time in between shots, conscious thoughts can enter the player’s mind and that hinders all the sensational aspects of racket manipulation and proper eye foot connections. I think players would benefit from forcing themselves to rush their shots and use any remaining mental faculty on deeper processing of the ball.

I think if you ever watch Federer practice sometimes he just hits a random two hander or slaps the ball flat or slices with an exaggerated motion. I think this comes from a place of creativity and deep presence that allows him to just play what he wants to play and that in the long run has made the racket an extension of his hand. I think practice should be the time to try all different types of shots and to use your conscious mind and a good coach to help you make it happen if you aren’t understanding how the racket should strike the ball on a particular shot. I think this is a function of court time and how much time a player spends on post shot processing in practice.

To supplement this, great athleticism, balance, mobility, coordination in throwing mechanics will set the physical limits for how consistently competitive those shots and receiving ability become.

February 22, 2026

I agree completely. In squash, players have a much better sense that every shot is an emergency, and your skill is defined by your ability to wield the racket to solve them. In tennis, we separate things into “forehand” “backhand” “serve” “running forehand” etc, etc, and while these categories do exist in some sense, in reality it’s the same as squash – each is just a manifestation of your skill in using the racket.

February 23, 2026

I do agree with Murtaza Khalil.

Once a tennis player has established a solid level of proficiency in terms of their shots, then consistency with those shots becomes the next “growth spurt” in their pathway forward.

The measure of progress is always subjective.

Adding variety of pace, spin, placement and flight.

Strokes are simply the tools of the game. The real skill is the mental ability to exert and absorb pressure, during a match.

Particularly at crucial moments of competition. The ebb & flow of battle.

As the saying goes: how you hit the ball is certainly important…where a competitor hits the ball is perhaps more so.

Most importantly, in my opinion, is the ability to enjoy the game. And understand the many benefits, the game provides to anyone playing regularly.

February 23, 2026

Agree 100% about enjoyment. Dopamine is a big player in motor-learning acquisition. You quite literally learn tennis better if you’re having fun. As for the “real skill” of tennis – I think this is a misunderstanding from watching pro tennis. At that level, everyone has their contact mapped. Everyone can move, everyone can see, everyone has baseline executive function. ONCE you have those foundations, then yes, skills like tactics and the ebb & flow of the match matter a lot, but for 99% of players, there are foundational tennis-playing skills that are categorically more important, which, for players on the pro tour, came so automatically they barely even realize they exist. The mental state Murtaza is talking about – where you treat every shot as independent, problem solve each one separately, and stay in the present moment, rather than in the past or future – is one such executive function skill. Many, maybe even most, intuitively approach the game that way from day 1. For those who don’t, though, this is a fundamental re-framing that must occur before high-level tennis can be played at all.