I can’t trust my forehand.

I’ve heard the above sentence more than any other when it comes to fixing the forehand. It’s an extremely common problem that I struggled with myself as a teenager for many years.

The fundamental problem, though, isn’t the lack of confidence itself, not directly. The problem is a mechanically flawed, non-fault tolerant stroke that shouldn’t be inspiring confidence.

Trust = Fault Tolerance

The typical player’s forehand stroke will fail unless executed perfectly; if said player executes their forehand even slightly wrong (for example, by slightly mistiming the ball or by slightly mishitting it), they are going to miss. Under those circumstances, of course the player doesn’t trust their stroke; it’s untrustworthy.

Your brain is smart – it’s lack of trust in your forehand, the reason it sends the “don’t be confident in this” signal as you go to hit, is that it should not trust a fault sensitive stroke to succeed consistently, especially under any sort of pressure.

On the other hand, a fault tolerant stroke is extremely trustworthy. Since the stroke will succeed in the face of a small fault, you can trust it even in cases where small faults are unavoidable, like when you’re tired or nervous. It is this property – succeeding when things aren’t perfect – that inspires your brain’s confidence.

Therefore, we improve your forehand confidence by improving the stroke’s fault tolerance. We’ll start by fixing the #1 fault tolerance destroyer on the forehand – changing your string angle through contact.

Some Quick Terminology

When I say “string angle,” I am referring to the angle between the strings and the ground. We refer to certain string angles as “open,” “neutral,” or “closed” depending on orientation.

Open string angle – strings angled up towards the sky

Neutral string angle – strings parallel to the net

Closed string angle – strings angled down towards the court

The modern forehand is hit with a slightly closed string angle, which is adjusted slightly depending on contact point and desired ball flight path.

Maintaining the String Angle

The string angle should barely change through the hitting zone. The longer you maintain your string angle through the hitting zone, the more fault tolerant your swing will be.

This is a simple case of collision physics. If a ball strikes an open racket face, it will deflect up more, and if it strikes a closed racket face, it will deflect down more. There is a certain range of string angles such that the ball will fly over the net and come down before landing out. In order for your forehand to work, you need to contact the ball while the strings are at an angle in this range.

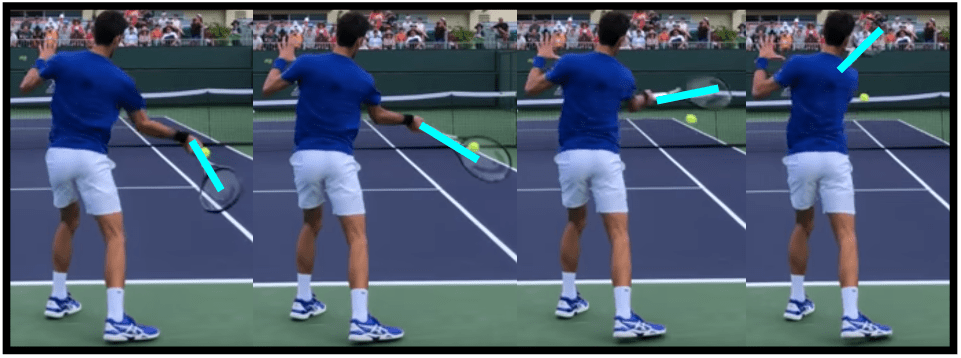

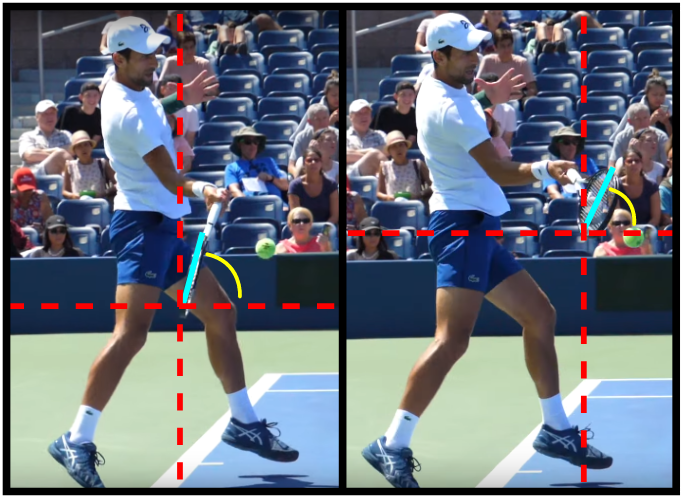

The longer you can maintain a correct angle through the hitting zone, the less precise you have to be with your swing timing. Look at Novak Djokovic’s forehand above – if he were to contact the ball in any of frame 2, 3, 4, or even 5, his shot would go in. His string angle is roughly the same for his entire hitting zone. This is just one of the many things he does that allows him to practically never miss.

What String Angle to Choose?

The lower the ball is, the more open your strings should be, and the higher the ball is, the more closed your strings should be. Again, this is simple collision physics – you want low balls to fly higher off your racket and high balls to fly lower off your racket.

The change in string angle between shots is very minor. On low balls, for example, topspin shots are played with a neutral or even slightly closed string angle, not an open string angle. There is a ton of frictional force pulling the ball up through contact; it’s not necessary to actually deflect the ball up at all, even on a low ball. Only topspin lobs require an open string angle.

I will reiterate – the most important aspect of string angle on any shot is that it is unchanging through contact. Whatever shot you’ve elected to hit, however you’ve decided to orient your string angle through contact, make sure that angle barely changes through the hitting zone.

Don’t Players Rotate Their Rackets?

Yes, but in a different plane, a plane which does not change their string angle through contact. Elite players rotate their rackets (passively) about their forearm through the hitting zone, not about the handle.

Look at the back view of Djokovic’s forehand above. The racket is rotating, but it’s rotating in such a way as not to alter the angle of his strings through contact. From frame 1 all the way to frame 4, his string angle is slightly closed. That string angle remains consistent, even though the racket whips around his forearm throughout the stroke.

Relaxation and String Angle

At first, it’s tough to relax your wrist and maintain your string angle. You have to pull the racket with your core movers at a pretty specific vector to avoid your forearm going crazy and rolling all over the place.

On the other hand, it’s very easy to maintain a consistent string angle with a tight wrist – this is why you naturally tighten up when you know you need to make a shot; your brain understands that a tight wrist isn’t ideal, but at least you’ll be able to maintain a string angle that will keep the ball in play.

But relaxation is the holy grail of forehand topspin and power, so it’s a worthy goal to practice your string angle maintenance with a relaxed wrist.

Shadow Swings

Shadow swings are the best tool for teaching yourself to maintain your string angle through contact.

The racket can (and often will) roll over during the follow-through, but throughout the hitting zone the string angle must remain constant.

Turn sideways, place your racket into its starting position for your forehand, and then lightly rotate your trunk and swing forward. Start at half speed and work up from there. Relax your hand, and swing out, up, and through an imaginary ball in front of you.

Observe your string angle through the hitting zone. Is it changing? The racket can (and often will) roll over during the follow-through, but throughout the hitting zone that angle must remain constant. Tweak the way you pull your arm with your chest until the angle is in fact remaining constant through the racket’s rotational whip.

You can add a small amount of tension with your hand/forearm to maintain the string angle, but ensure that your wrist is still loose enough that, when you initiate your rotation, your racket naturally lags behind your hand, and then flicks around your forearm as you swing.

Ensuring Shadow Swings Translate

Additionally, ensure two things on your shadow swings:

- Your hips get all the way around (back to parallel with an imaginary net) each swing. Don’t leave them under-rotated.

- Your imaginary contact point is out in front of and laterally away from your body.

It’s very easy to lose those two points when you’re not hitting a real ball, but in order for the shadow swings to translate, we need to ensure specifically that these two good habits stay ingrained.

The Angle Actually Changes a Little

You’re tweaking your shadow swing, and you finally find a comfortable, whippy, natural feeling swing where the string angle isn’t changing very much through the hitting zone. You notice, though, that despite your best efforts, the angle is still closing a little as the racket comes around.

That’s fine. On a correct forehand, the string angle typically does roll over a very small amount through the hitting zone. This is a very muted effect and it certainly isn’t volitional.

Let me clarify the three differences that distinguish this small, acceptable angle change from the typical one that destroys the forehand’s fault tolerance.

1. It’s Non-Volitional

This angle change happens completely naturally as a result of other forces during the swing. The player is not at all trying to change their string angle through contact – they aren’t trying to “roll their racket over the ball.”

That means that this angle change never results in any unnecessary tension in the wrist, never hampers racket head speed, and naturally adjusts itself appropriately based on the exact situation of the stroke.

2. Correct Angle is a Range

There does not exist one specific string angle at which the stroke must be contacted. Rather, there exists a range of correct angles, contact at any of which will lead to a decent shot.

A slightly closed angle will cause the ball to fly lower over the net, and land shorter, while a slightly open angle will cause the ball to fly higher over the net and land deeper. But that doesn’t mean you’ll miss.

The small angle change that occurs naturally isn’t big enough that the angle of your strings leaves this acceptable angle range – it’s still the case that if you’re a little early, or you’re a little late, your stroke will succeed. As a result, your stroke is still fault tolerant, and thereby still trustworthy.

3. Contact Height Effects Desired String Angle

On a typical shot, the ball is moving down through the hitting zone and racket is moving up through the hitting zone. In this situation, the very slight angle change through contact can actually help the ball stay in when the swing is mistimed.

If you contact the ball early in the swing by accident, that also means you contact the ball higher, and in that case you actually want a slightly more closed string angle. And, similarly, if you contact the ball late by accident, you’ll contact it lower and want a slightly more open string angle. (This is different if you’re hitting on the rise, one of the reasons that shot’s degree of difficulty is higher.)

Just Get Rid of the Bad Habit

I only mention fact that a very small angle change does occur so that you don’t happen upon a correct swing and think that it’s wrong. When you relax your hand, rotate your body, swing out, up, and through, and hit the ball in front of you, the small change will occur completely automatically, without you having to think about it.

All I really want is for you to understand the role that string angle plays in fault tolerance and to find the swing path that causes it to remain mostly constant through the hitting zone. Any very small string angle change that still occurs, without you focusing on it, won’t effect your swing’s fault tolerance.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, we have the large, fault tolerant killing string angles change that most players unintentionally employ. These changes are volitional; the movements are usually bad habits that transpire due to intentional effort by the player to do something like “roll your racket over the ball.”

That’s what we have to get rid of. That’s what’s killing your forehand’s fault tolerance.

Restore that fault tolerance, and you restore your confidence.

July 20, 2021

Really enjoying your articles!

Having some trouble though with the following phrase:

“and then flicks around your forearm as you swing.”

Flicks makes me think of the wrist going into flexion like a pinball flipper which of course changes the string angle.

July 21, 2021

Right. What matters is the axis around which the racket rotates.

If you look at the picture of Novak’s racket rotation, you’ll see the kind of rotation that we’re aiming for: about the axis of the forearm.

Novak’s racket-arm angle does unwind a little bit, but not too much, and his string angle does close slightly through contact, but, again, not that much.

The wrist only goes into flexion once the swing is well into the follow-through phase.

July 21, 2021

Thanks for the reply 🙏

I’m still struggling visualizing the following (it’s that proprioception thing I suspect)

“What matters is the axis around which the racket rotates. If you look at the picture of Novak’s racket rotation, you’ll see the kind of rotation that we’re aiming for: about the axis of the forearm.”

“Elite players rotate their rackets (passively) about their forearm through the hitting zone, not about the handle.”

Is their a simple isolation exercise(s) that you can suggest to cement this as mental image and feel to acquire, the racket axis rotation? Or maybe a followup article on this very important concept. I suspect that it may be confusing for many learners. Words can be ambiguous. Another series of photos highlighting this rotation may also help.

Great stuff! Appreciate your thoughts 💭

July 22, 2021

After retreading this section a number of times AND going on court with these new swing thoughts 💭 it’s all starting to make more sense and come together.

The challenge with reading about biomechanics and physics is “transference” is much more difficult than casual reading and even some lighter forms of academic reading 📖.

Would it be okay to ask where you’re located and perhaps a little about your background?

July 23, 2021

Yep, it is tough. I should specify that much of what I write is meant for coaches, or for you while watching video of yourself. While actually on the court, focusing on the biomechanics themselves typically leads to information overload, and thereby harmful tension that prevents the very swing we’re trying to create.

Currently, I teach at the Nassau Tennis and Racket Club in Princeton, NJ.

July 26, 2021

Exactly, it’s what makes tennis so challenging, much of learning solid stroke mechanics is “counterintuitive” and focusing on biomechanics on court is counterproductive. “Paralysis by analysis”. The #1 enemy of good strokes, unnecessary “tension”.

July 27, 2021

Here’s a quick biomechanics question regarding the shoulder/chest rotation referencing the 5 frame photos of Djokovic in the Maintain the String Angle section. In frames 1,2, and 3 you can see his left shoulder, however in frames 4 and 5 you cannot. Doesn’t this suggest that his shoulders rotated through contact and didn’t stop once they faced the net suddenly to accelerate the arm?

July 28, 2021

Technically that’s true, but it’s really not that important. Relaxation and consistency are more important than full stopping at contact. I’m more referring to two specific cases when discussing not over-rotating:

1. Some players spin around so much that they face their non-hitting side by their follow-through. A better aimed twist, trying to stop roughly by the target, would be far more efficient.

2. To encourage players to hit inside-out by slightly prematurely stopping their rotation (only if they have an issue with inside-out. Some people do this automatically just by “aiming” there).

The fact that there’s still a small amount of rotational velocity through contact is a very minor thing.

July 27, 2021

If you look at contact for most well hit pro FH’s, it is often the case where the hitting shoulder is in front of the non hitting shoulder at contact which promotes making contact in front of the body. Is this a teaching/coaching point in your opinion? The challenge is that we cannot see the direction the ball is going in these photos.

July 28, 2021

You’re correct about the joint angle. I’ve found most players do this naturally, so it’s not a common coaching point. Once a player is driving with their hips and abs, and turning their entire upper body as a unit, and attempting to stop their rotation approximately at their target, usually the arm and shoulder flick forward like that without conscious effort.

July 29, 2021

I picked this off of a forehand wrist thread at Tennis-Warehouse as it deals with the wrist position for rotating the racket and includes pics. I am unfortunately unable to achieve the laid back positions as demonstrated here and therefore cannot rotate the racket. I believe being able to achieve at least 70degrees of extension is critical, 90degrees is better, and more than 90 even better to create power and spin production. Most people can get at least 70degrees. If you see someone struggling to get spin, check on their wrist extension range to see if that could be the problem. See below:

“I think this motion is what has many people confused when they talk about wrist snap, but its actually mostly a forearm rotation.

When the wrist is in a neutral position like this its easy to separate from the forearm and the wrist becomes the only moving part left and right and you can “SNAP THE WRIST” like some people say (you can also SNAP THE WRIST forward and backwards, but thats not important here):

http://shrani.si/f/34/zs/2K9ZhUVR/20170405224851.jpg

http://shrani.si/f/w/kG/3XHMs2oX/20170405224854.jpg

But when the wrist is laid back, like it always is with a proper stroke mechanic and relaxed arm, and the wrist lags behind, then when you use this rotational force you mostly rotate ur forearm and a biproduct of that is that your wrist also rotates, you can’t really rotate your wrist separately as a unit:

http://shrani.si/f/24/rV/2jeUVn6O/20170405224921.jpg

http://shrani.si/f/o/ys/oywCpqS/20170405224926.jpg

http://shrani.si/f/2R/Vp/OMbztel/20170405225004.jpg

http://shrani.si/f/3R/dD/24K92j1u/20170405225015.jpg

At first glance it might look like you use ur wrist, because it turns, but so does ur forearm.”

So this rotational movement is not really a WRIST SNAP, but its a FOREARM ROTATION, thats why I think the term WRIST SNAP might confuse alot of people and they will try to implement a true wrist snap and therefor will break down their swing completely, lose the lag and try to snap and turn the wrist.

July 30, 2021

Yes, “wrist snap” is very misleading when used as a starting point for instruction, for the reasons you described. I’m pretty sure I said this on one of our other comment chains, but might as well reiterate here: a lot of wrist rotation is the wrist, hand, and forearm all rotating together. There is some ulnar deviation on many shots, but not all.

The wrist itself is mostly acting as a hinge to allow seamless force transfer to the racket. The forearm is most certainly not tensing in order to create any sort of wrist motion, and I agree with you 100% that many players who hear “wrist snap” try to use their forearm muscles to create force, rather than just stabilize.

July 31, 2021

Very true, the term “wrist snap” can mislead players into thinking a forced and deliberate wrist flexion movement is needed to accelerate the racket into contact in order to create power and spin. Once that stroke/swing thought becomes a habit it is very difficult to correct. Agree, the forearm, hand and wrist mostly rotate as a unit. However, without adequate wrist extension it is difficult to stabilize the racket and prevent the wrist from going into flexion too soon. Have you dealt with players who “snap the wrist forward to try to create racket head speed? If so, what corrections did you find helpful?

BTW, I tested that wrist control device with some players that have advanced forehands and they couldn’t hit the ball, they complained that it “locked up” their wrist. However, they already have very good forehands. Also tried it on a low intermediate player, again a similar complaint about arm/wrist tension. Leads me to believe it has limited corrective value/benefits.

August 1, 2021

Thanks for the report about the wrist control device.

Yes, intentional flexion is a very sticky habit. With the last girl I worked with who had this exact problem, it took a month of twice a week lessons before she was able to re-wire her brain to manipulate the racket in space properly. (This is actually the girl referenced in The Fault Tolerant Forehand).

Lots of mini tennis helps. By the end of our lessons together, she loved mini-tennis, because she finally felt like she could actually accomplish what she wanted to with her racket. Mini-tennis happens at such a slow speed, and with such slow balls, that it’s much easier for a player with a bad habit to spend all of their focus relaxing and erasing that habit.

Also, mini-tennis is the least stressful if the player (like this girl) has already developed a bit of a nagging forearm/wrist injury from the intentional flexion. Since you’ve read the book, you already know this, but just for the sake of the comment thread I’ll repeat it again: the key is to learn the proper arm swing at a slow overall speed, without using much rotation, then dial it up with more and more explosive body rotation while maintaining the same relaxed arm movement.

October 4, 2022

What if we taught the wta forehand instead, which is easier to learn and will likely still benefit the majority of the readers here who are not in the professional league?

Are we really that delusional to think that we have the comparative eye-hand coordination and athleticism required to pull off a Roger Federer—or for that matter any professional player—forehand? Not to mention generate enough momentum from our moving body parts to impart to the ball?

October 8, 2022

The “ATP” forehand doesn’t require professional level coordination or athleticism to execute.

It’s essentially just throwing the racket, sidearm, through the ball. Getting the kinetic chain correct is difficult, but after doing so you can produce far more velocity with less effort, so, yes, it’s a worthy goal for players to strike the forehand this way.

I actually have some students who play baseball, and for them this stroke comes extremely naturally. For others, it takes more time, and more work with weighted swings, but they get there, and their velocity greatly improves, without a corresponding decrease in consistency.

October 4, 2022

Also lest we forget, 2 of the best forehands the ATP has seen belong to Robin Soderling and Del Potro who have WTA forehands.

October 8, 2022

If you classify the forehands of Soderling and Del Potro as “WTA,” then WTA vs ATP doesn’t relate to much of the content on here.

Both players use the same, efficient kinetic chain we talk about here: hips -> abs -> chest -> hand rotation.

Both power the swing with their core movers, both have, fundamentally, a sidearm throwing motion through contact. Del Potro often makes heavy use of gravity, and Robin often rotates his abdomen WELL away from the ball during preparation.

Of course, we see both of those forehands as high quality, efficient movements, and if a player presented with those tendencies, they’d never be coached otherwise if it was working.

November 19, 2022

Could you elaborate a bit more when we want to hit on the rise?

Thank you so much!

November 19, 2022

Sure. When you hit on the rise, the ball is moving up as you strike it, instead of down. This means that if you use your typical string angle, you’ll sail the ball long.

You actually need to close your racket face more when hitting a ball that’s moving up. You still want to keep the angle consistent throughout the stroke, so that if you mis-time the ball slightly, it still goes in. The only difference is that the string angle that’s maintained is more closed to the court.