What do Karue Sell and Scott Adams have in common?

Believe it or not, both have addressed a very common, often misunderstood match play decision:

When should I take my forehand up the line?

Scott frequently competed against a friend whom he could never beat. One day, he realized the reason: His friend would bait him into low percentage, down-the-line attacks. It looked like there was space down-the-line, so Scott would attack there, but the shots Scott would attempt were so difficult that he’d miss, and miss, and miss.

So what’s the solution? Don’t go down the line, of course!

Not so fast.

Ex tour player Karue Sell gives us a more nuanced analysis.

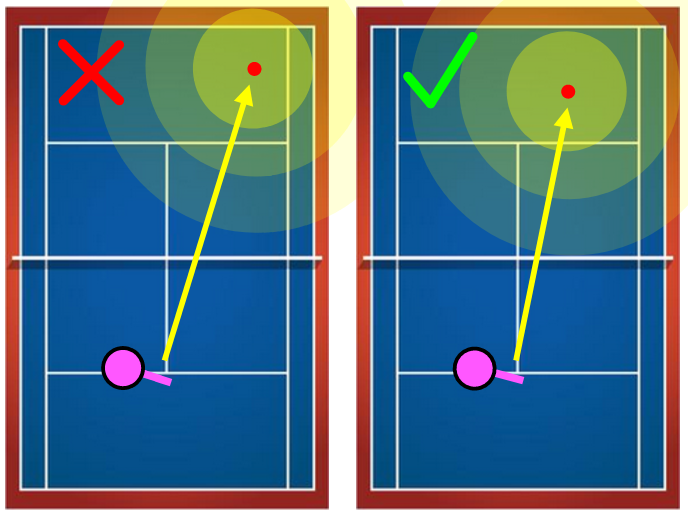

There are two distinctly different goals a player can have when changing direction using a down-the-line forehand. One is to attack, but the other is merely to change the pattern of the rally. When attempting the second, the shot is hit higher over the net, and farther from the lines, making it almost as high percentage as a cross-court forehand.

We’ll be using the down-the-line forehand, probably the most common decision point in singles tennis, as the substrate to discuss the difference between two different fundamental kinds of misses:

- Bad decisions

- Bad execution

While trying to work misses out of your game, you need to know which category you’re in, because the best ways to minimize each kind are very different.

So You Missed Down-The-Line…

As coaches, we see this all the time. Our students are hitting great, heavy balls cross-court, and then, all of the sudden… a down-the-line miss for, what seems to us, no reason.

But was this really a Bad Decision miss? What if our student simply wanted to change the pattern of the rally, and only missed due to Bad Execution?

Bad Decisions

A true Bad Decision has two hallmarks:

- You struck the ball well

- It was close

Bad Decisions are balls that land a few inches long, a few inches wide, or hit the top of the net.

Since you’re here, I know you’ve designed your game to be fault tolerant, and that means that any time you strike the ball well, it should go in. Sometimes you’ll shank it off the frame, and in that case, even a fault tolerant stroke will miss, but when your execution was precise enough to create solid contact near the center of the string bed, well, that needs to be good enough.

If you are frequently missing close while making clean contact, you’re aiming to bad targets.

If you’re hitting into the net, aim higher, and accelerate 10% less to compensate.

If you’re hitting long, just dial down your velocity by 10% (or perhaps just loosen your grip, if you notice you’re tight).

If you’re missing wide, aim farther into the court.

We talk a lot about technical fault tolerance, but we also need tactical fault tolerance. We need to select shots such that, when we mis-execute them by a little bit, they still go in.

So, was our student’s down-the-line miss a Bad Decision? Well, how close was it, and how clean was the contact?

If it landed two inches wide, and it was well struck, then, almost certainly, had our student simply aimed a little farther into the court, the ball would have gone in. Similarly, if their down-the-line attempts frequently land 3-6 inches long, simply dialing down the acceleration by 10-20% should vastly improve their miss-rate.

We talk a lot about technical fault tolerance, but we also need tactical fault tolerance.

But what if the ball was hit into the back curtain? What if it was shanked onto the next court? This miss has nothing to do with the target. No matter where they’d aimed, the movement pattern they executed wasn’t sending the ball back into the court.

It was a Bad Execution miss.

Bad Execution

Even for a fault tolerant tennis game, execution matters. If you slightly mistime, or mis-execute your stroke, it should still work, but sometimes, you will make bigger mistakes than that. The more fault tolerant your game, the more execution faults you can handle, but some faults will be so large that you’ll just miss anyway.

Very rarely should you adjust your tactical game based on acute Bad Execution.

Imagine you’ve just hit your down-the-line forehand into the back curtain. As we’ve already discussed, this result did not show the hallmarks of a Bad Decision miss. It wasn’t a well-struck ball that landed close to its target – it was a poorly struck ball that wasn’t close at all.

So what would it look like if you tried to eliminate this miss by adjusting your decision making?

If you hit it 20% slower, the shot wouldn’t have hit the back curtain, but it still would have been way out. What about 30% slower? Half speed? Just rolled the ball in?

Very rarely should you adjust your tactical game based on acute Bad Execution.

The level of adjustment required to make a Bad Execution miss succeed instead is large. To eliminate these misses using shot selection requires selecting shots that are very far below the level that your good execution can handle.

This cedes a lot of ground. If you adjust this way, then even when you do execute well, you won’t get your usual payoff. All your shots are now slow, aimed right down the center, or both. More of your mishits will go in, but is the trade-off worth it?

So How do I Stop Missing?

Bad Decision misses are pretty easy to work out mid-match.

“On most of my down-the-line shots, I’m hitting it well, but the ball is landing long.”

Solution? Hit a little softer. The same attempts that used to go long will now fall in, and you’ll stop losing points from neutral and offensive situations.

Acute Bad Execution misses are also pretty simple. If you execute a shot poorly once or twice, accept it, breathe, relax, and move on to the next point.

Chronic Bad Execution misses, on the other hand, are much more difficult. When a certain execution mistake is happening over, and over, and over again, some adjustment will be necessary to remain competitive.

“Half the time I go down-the-line, I forget to watch the ball, and I shank it onto the next court.”

You can remind yourself to watch the ball, and if that works, great, but, chances are, you haven’t built enough of a habit of watching the ball to do it consistently. Make a mental note to work on that in practice, later.

As for the actual match, you can either:

- Accept your 50+% miss rate down-the-line (probably a bad option)

- Bring your swing velocity way down in hopes of cleaner contact even with sloppy vision

- Stop hitting down-the line

A mix of 2 and 3 is probably best. Your issue here isn’t one of decision making. It’s that you simply cannot execute this down-the-line shot at a match ready frequency. The sooner you accept that uncomfortable fact, the sooner you’ll adjust to give yourself a chance in spite of it.

Overlap

There’s one place where Bad Decisions and Bad Execution overlap: selecting a shot you’re simply not good enough for. Here, the miss will look like Bad Execution, but really it was a Bad Decision.

I see this all the time on passing shots, specifically. A student will go for a ridiculous Rafa Nadal, full sprint, over the head follow-through, topspin passing shot, and miss onto the next court.

You can call this an “execution miss,” and for a player with a good running forehand, it actually could be, but for most of my students, this is a Bad Decision masquerading as Bad Execution. Yes, technically, if they’d executed the shot perfectly, it might have won the point, but in reality something like a lob, or simply trying to get the ball low to the net player’s feet, had far more equity.

Learn your own game. Everyone has different strengths and weaknesses. You might have shots that no one except you should be selecting, and yet you typically execute them well. If you miss one of those, don’t worry about it, and go back to the well next time.

On the other hand, be honest with yourself about the shots you’ve never been able to execute consistently, and relegate those to the practice court until they improve.